(IBNS): The largest human migration in history occurred between 1834 and 1923 when the British in its experimental bid to abolish slavery brought mostly Indians as indentured labourers to work in the sugarcane estates of Mauritius. Sujoy Dhar visits the historic Aapravasi Ghat, an immigration depot in capital Port Louis, to retrace the footprints of some half a million people who landed there over nearly a century in quest for a better future.

The wind is rising and we must make sail. Anchors aweigh! We must be off!

Sea of Poppies, Ibis trilogy, Amitava Ghosh.

For the aspirational, upwardly-mobile millennial Indians getting hitched, Mauritius is synonymous with the grand idea of an affordable yet exotic tropical island honeymoon that combines beaches, turquoise blue waters and uber cool resorts offering seclusion amid that boho-chic vibe.

But Mauritius is actually much more than that. Behind the popular bucketlist image of its turqouise waters, lies history – the world history of colonialism which was rewritten here with the British beginning their great experiment of transition from slavery to indentured labour practice.

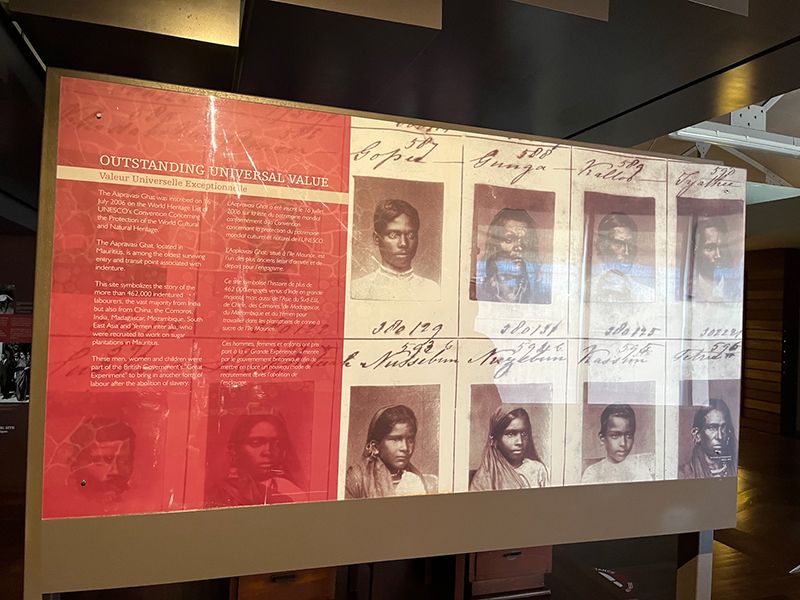

And where else can one relive that troubled history of the 19th century and its transition than at The Aapravasi Ghat Immigration Depot in Mauritius capital Port Louis. This site by the harbour is where from where the modern indentured labour diaspora (mostly from India) emerged. Recognising the Immigration Depot’s role in social history, UNESCO declared it a World Heritage Site in 2006.

In 1834, the British Government chose the island of Mauritius as the first site for its ‘the great experiment’ in the use of ‘free’ labour to replace slaves. Between 1834 and 1920, almost half a million indentured labourers arrived from India at Aapravasi Ghat to work in the sugar industry of Mauritius, or to be transferred to Reunion Island, Australia, southern and eastern Africa or the Caribbean.

From the ports of Bombay, Madras and Calcutta those who embarked for these voyages of destiny were mostly from the then Indian states of Bihar, Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala and Bombay.

While the majority of indentured labourers came from India, there were also people from China, South East Asia, Madagascar and East Africa.

“The site is a vivid testimony of the tribulations of our ancestors to shape our modern, multi-ethnic and peaceful society. They are the builders of our nation and are at present at the helm of all walks of life of our society,” says Mahfooz Moussa CADERSAIB, Lord Mayor of Port Louis.

According to UNESCO, the buildings of Aapravasi Ghat are among the earliest explicit manifestations of what was to become a global economic system and one of the greatest migrations in history.

Those who have read Amitava Ghosh’s Sea of Poppies, the first volume of his historical fiction trilogy Ibis, are aware of the character of Deeti, the determined but hapless wife of a crippled opium-addicted opium factory worker. She was forced to escape from the village with the untouchable caste ox man Kalua and the two became indentured labourers sailing on the ship Ibis to the distant land of Mauritius from Calcutta.

Ghosh’s novel is set on the time when the East India Company was minting money from the opium trade between its Indian dominion and China (1830s).

(Re)inventing a People on the Sea: Instances of Creolization in Amitav Ghosh’s Sea of Poppies, an article by Ahmed Mulla, an Associate Professor of English at Université de Guyane and migration expert, puts it thus: “…it was also the time when many in the colony, ruined by the compulsory cultivation of opium to the detriment of traditional agriculture that guaranteed self-reliance, or condemned by social prejudice, were left with no other option than to seek a future elsewhere.”

“Forced to share a confined place during a lengthy boat trip to an unknown destination in the Indian Ocean, people of opposed social and cultural backgrounds had to adjust to the unwritten laws of a community formed by chance,” he wrote about the characters of Sea of Poppies, who belong to the early waves of indentured workers that travelled throughout the Indian Ocean.

Cut to the present day tourist attraction that is Apravasi Ghat complex now in Port Louis. It now stands as a symbol of Mauritian identity since the ancestors of more than 70 percent of today’s Mauritian population arrived on the island through this immigration depot. The indenture period in Mauritius was 1834 to 1910.

As you walk into the compound by the port, a footprint plaque commemorating the history of indentured labourers greet you.

According to the centre (with a museum and the old historical buildings by the harbour), the British Parliament’s decision to abolish slavery in its colonies in 1833 led to the setting up of a new system of recruitment called indenture.

An indentured labourer was a free man or woman who signed a contract to work away from his/her homeland for an employer for a specified period of time, generally for five years. Labourers’ contracts specified their terms of employment and outlined their general standard of living, wage rate, working hours, type of work, rations, housing and medical care.

In Mauritius, even before the abolition of slavery on 1st February 1835, planters called for labourers as the sugar industry expanded rapidly.

The British colonial Government wanted to evaluate the viability of this new system and also sought to demonstrate the superiority of free over slave labour. The “Great Experiment” was launched in Mauritius as a test case. The experiment started when the ship Atlas arrived from India with 36 indentured labourers on board on Nov 2, 1834.

Between 1839 and 1842, the emigration of indentured labourers from India was suspended as a result of the abuse to which the earliest contract workers in Mauritius were subjected.

Indentured immigration peaked between 1843 and 1865 to respond to the increasing needs of the sugar industry in Mauritius, the most productive sugar colony in the British Empire around 1845. Indentured immigration declined from the 1870s and came to a formal end in 1910.

According to the centre, before the construction of the Aapravasi Ghat in Trou Fanfaron in Port Louis, several buildings were used as depots in Port Louis to receive indentured labourers. You can find these structures here, including a hospital complex for indentured labourers.

The Aapravasi Ghat was constructed in 1849 to improve the management of indentured immigration. The depot was enlarged in the 1850s and 1860s to receive the increasing flow of immigrants. By 1860, the immigration depot was extended to a carrying capacity of 600 immigrants.

The role of Aapravasi Ghat immigration office was to receive newly arrived labourers, perform sanitary control, register immigrants and time-expired labourers, deliver tickets and passes to immigrants, allocate labourers to sugar estates or public construction projects, etc.

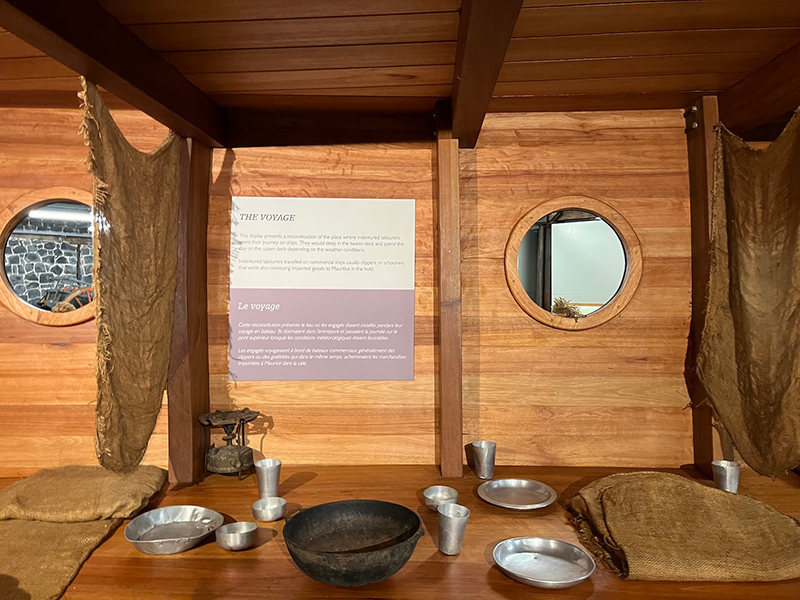

The journey from India to Mauritius by ship those days took eight to ten weeks. When the labourers arrived at the Aapravasi Ghat, they were fed and housed and given medical care if necessary.

When the immigrants arrived, they were inspected by the medical officer. He vaccinated those who had not already been vaccinated for smallpox. If a case of smallpox or contagious disease was found, the whole number of passengers were sent to quarantine stations on small islets around Mauritius.

Among the buildings here are a Rice Store, a Military Hospital Complex and a Civil Hospital. As you walk through the buildings, you relieve the history of a bygone era when our ancestors were looking for a better life in a distant land like Mauritius.

One of the early accounts of indentured labourers is one penned by historian Satyendra Peerthum about a Bengali Indian seasonal worker and sirdar (overseer of the labourers) called Mohun who in 1837 at the age of 38 arrived in Port Louis to work in a sugar estate. He served a five year contract and then went back to India (Bengal) and became a job contractor recruiting indentured labourers for Mauritius sugar estates.

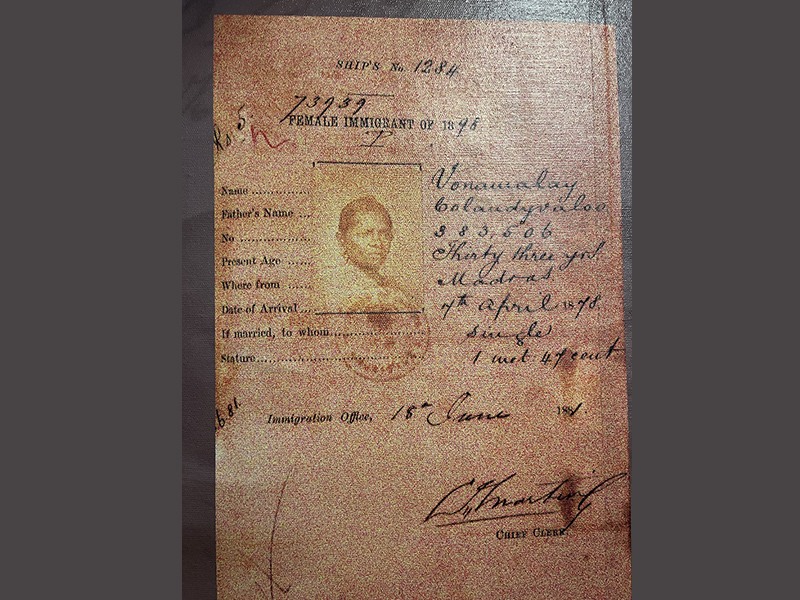

In 1865, a photographic unit was created and a photographer took two portrait photos of each immigrant. One was attached to the immigrant’s ticket while the second photo was retained in the records office of the Aapravasi Ghat. These documents are now kept at the Mahatma Gandhi Institute.

Inside the museum now, one can not only learn the story of that nearly a century long migration, but also the lifestyle of the men and women who came with the hope of a new life. So the replica of a ship, the mock-up kitchen or the hut in which they lived throw light on the hard life of the labourers.

A visit to Mauritius for an Indian is never complete without a homage to Apravashi Ghat.